Confronting Genocide Never Again Darfur Violence and the Media

Affiliate I: Challenges and Choices

It was old round midnight in a little village in southern Sudan, and the only link to the rest of the world within a v-hundred-mile radius was one satellite phone, and so when it rang it was a scrap of a shock to everyone.

Don dispensed with the formalities. "My human being, you are not easy to detect."

"Obviously, hiding from you is non as easy as I idea," John countered.

Despite his endeavor at a cool demeanor, John was excited. After Marlon Brando and Mickey Rourke (John is well aware that he has bug), Don was his favorite thespian, and the fact that the two of them were nigh to get on a trip together to Chad and across the edge into the western Sudanese region of Darfur was firing him upwardly.

However, Don wasn't making a social telephone call. He was concerned that the mission that nosotros were going on with a agglomeration of members of Congress was only going to spend several hours in the refugee camps in Chad, and he wanted to stay longer. "Yous gotta rescue it," Don instructed John.

John looked around to see what tools he had at his disposal in that footling southern Sudanese village, simply all he could hear was the ribbit, rabbit of the Sudanese frogs. "I am in the heart of nowhere. Give me twelve hours."

A few hundred dollars of satellite phone calls later, a much more than substantial and lengthy trip was planned. We as well managed to go Paul Rusesabagina, whom Don had portrayed in Hotel Rwanda, and Rick Wilkinson, a veteran producer for ABC's Nightline, to come with u.s. and assistance interpret and chronicle our first journey together.

Our trip to witness the ravages of genocide in Darfur was non the commencement castor with that heinous crime for either of united states. Don had visited Rwanda post-filming, and John had been in Rwanda and the refugee camps in Congo immediately after the genocide.

As nosotros listened to the stories of the refugees who fled the genocide, we sensed what it might feel like to be hunted as a human being beingness. These Darfurians had been targeted for extermination by the regime in Sudan on the basis of their ethnicity. Although well-meaning and thoughtful people may disagree on what to call it, for usa the crisis in Darfur is ane that constitutes genocide.

Enough is Enough. Nosotros need to come together and printing for action to cease the violence in Darfur and forestall hereafter crimes confronting humanity. Through elementary acts and innovative collaborations, we tin save hundreds of thousands of lives now.

That is our fervent hope, and our goal.

Darfur: A Slow-Motion Genocide

Genocide is unique among "crimes against humanity" or "mass barbarism crimes" because it targets, in whole or in part, a specific racial, religious, national, or ethnic group for extinction. According to the international convention, genocide tin include any of the following five criteria targeted at the groups listed above:

-killing

-causing serious actual or mental impairment

-deliberately inflicting "conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in function"

-imposing measures to prevent births

-forcibly transferring children from a targeted group.

The perpetrators of genocide in Rwanda took i hundred days to exterminate 800,000 lives. This was the fastest rate of targeted mass killing in human history, three times faster than that of the Holocaust.

JOHN:

In mid-2004, ane year into the fighting and six months before the trip Don and I took to Republic of chad/Darfur, I went with Pulitzer Prize–winning author Samantha Power to the rebel areas in Darfur. At the same time, U.South. Secretary of State Colin Powell was visiting regime-held areas in the region. Just different Secretarial assistant Powell, Samantha and I went to the role of Sudan that the regime didn't desire anyone to see, and for very good reason.

Before the genocide, Darfur was ane of the poorest regions of Sudan, and the Saharan climate made eking out a living an extreme challenge. But these difficulties only made Darfurians hardier and more cocky-reliant, mixing farming and livestock rearing in a complex strategy of survival that involved migration, intercommunal trade, and resource sharing.

It had been over a year since the genocide began, so Samantha and I expected certain evidence of mass destruction. And we were indeed witness to burned villages where livestock, homes, and grain stocks had been utterly destroyed, confirming stories we had heard from Darfurians at refugee camps in Chad.

Withal no amount of time in Sudan or work on genocide ever prepares anyone sufficiently for what Samantha and I saw in a ravine deep in the Darfur desert — bodies of nearly two dozen young men lined up in ditches, eerily preserved by the 130-degree desert heat. Ane month before, they had been civilians, forced to walk up a colina to be executed by Sudanese government forces. Harrowingly, this scene was repeated throughout the targeted areas of Darfur.

We heard more refugees in Chad draw family and friends beingness stuffed into wells by the Janjaweed in a twisted and successful attempt to toxicant the water supply. When we searched for these wells in Darfur, we plant them in the exact locations described. The just difference was at present these wells were covered in sand in an try to cover the perpetrators' bloody tracks. With each subsequent trip to Darfur, I have found the sands of the Saharan Desert slowly swallowing more of the evidence of the twenty-first century's first genocide.

To u.s.a., Darfur has been Rwanda in tiresome motility. Perhaps 400,000 have died during iii and a one-half years of slaughter, over 2 and a quarter million have been rendered homeless, and, in a specially gruesome subplot, thousands of women accept been systematically raped. During 2006, the genocide began to metastasize, spreading across the border into Chad, where Chadian villagers (and Darfurian refugees) have been butchered and even more women raped by marauding militias supported past the Sudanese regime.

Sadly, the international response has also unfolded in slow motion. With crimes confronting humanity like the genocide in Darfur, the caring earth is inevitably in a deadly race with time to relieve and protect as many lives as possible. In the fall of 2004, after his visit to Sudan, Secretary Powell officially invoked the term "genocide." He was followed shortly thereafter by President Bush. This represented the first time an ongoing genocide was called its rightful proper noun by a sitting U.S. president. And yet in Darfur, as in most of these crises, the international community, including the United states of america, responded principally by calling for stop-fires and sending humanitarian aid. These are important gestures to be sure, but they do not stop the killing.

We believe it is our collective responsibleness to re-sanctify the sacred postal service-Holocaust phrase "Never Again" — to get in something meaningful and vital. Not just for the genocide that is unfolding today in Darfur, but likewise for the next attempted genocide or cases of mass atrocities.

And there are other cases, to be certain.

Correct now, we need to practice all we can for the people of northern Uganda, of Somalia, and of Congo. Though genocide is non being perpetrated in these countries, horrible abuses of human rights are occurring, in some ways comparable to those in Darfur. Militias are targeting civilians, rape is used as a tool of war, and life-saving aid is obstructed or stolen by warring parties. Furthermore, by the time yous pick up this book, another office of the world could take caught on burn, and crimes confronting humanity may be existence perpetrated. We need to practise all we can to organize ourselves to uphold international human rights constabulary and to foreclose these most heinous crimes from e'er occurring.

That is our challenge.

Raising the Political Will to Confront Crimes Against Humanity

Preventing genocide and other mass atrocities is a challenge fabricated all the more hard by a lack of public concern, media coverage, and constructive response, especially to events in Africa. Crimes against humanity on that continent are largely ignored or treated as function of the continent's political inheritance, more and then than in Asia or Europe. The genocide in Darfur is competing for international action with man rights emergencies in Congo, Somalia, and northern Republic of uganda --conflicts that along with southern Sudan accept left over 6 million expressionless — but the international response to these atrocities rarely goes beyond military observation missions and humanitarian relief efforts, which are bereft Band-Aids.

Crises like these need the immediate attending of a new constituency focused on preventing and against genocide and other crimes confronting humanity. Of these four conflicts, only Darfur has generated sustained media and public attending. Images of innocent Darfurian civilians — men, women, and children — hounded from their homes by ravaging militia take triggered pregnant activism on the office of Americans and citizens around the globe. But these public expressions have not, by the time of this writing, at the end of 2006, yielded a sufficient international response. The United States government has yet to take bold action to protect the victims, build a viable peace procedure, and hold those responsible for this genocide answerable.

At that place is some positive momentum building. At the Un World Summit in 2005, member nations agreed to a doctrine called the Responsibility to Protect, or R2P. R2P states that when a authorities is unable or unwilling, as is the case with Sudan, to protect its citizens from mass atrocities, the international community must take that responsibility. We believe that this doctrine, developed by a high-level panel cochaired by Gareth Evans (the president of the International Crisis Group, where John works) and Mohamed Sahnoun (old Algerian diplomat and United nations special advisor) commits us all, as individuals and nations, to do our function to fulfill that responsibility.

During our visit to Darfur and the Darfurian refugee camps in Republic of chad, nosotros heard story afterwards story of mind-numbing violence perpetrated by the Sudanese government ground forces and the Janjaweed militias they support. We heard of women being gang-raped, children existence thrown into fires, villages and communities that had existed for centuries being burned to the footing in an effort to wipe out the livelihoods and fifty-fifty the history of those communities. We heard things that just should not be happening in the twenty-get-go century.

In 1 of the refugee camps in Republic of chad in 2005, we met Fatima, forty-two, who described how she had to escape her village of Girgira in western Darfur after her mother, husband, and five children were all killed by the Janjaweed militias. She said she feared the government would impale her as well. In desperation, she walked for seven days to a refugee camp. She couldn't walk during daytime hours because of the Janjaweed gangs. She hid under trees and plants. Despite all this, she wanted to return dwelling house, simply she wanted to be sure it was safe. Having lost everything, she no longer trusted anyone, even the African Union troops deployed in Darfur.

Omda Yahya, a tribal leader we talked with from Tine, also saw all his children dice in a vehement raid on his town and in the subsequent escape to "safety." His boondocks, he says, was attacked by men on horseback, planes dropping bombs, and armies on human foot. He fled with many of his tribe, and subsequently more than than 15 days of walking without food or beverage, they arrived at a refugee camp. "We lost our hamlet. They burned it. If we get all our possessions back, so after that we can become dorsum. But at present we don't think information technology is safety to go dorsum."

How do we reply to these horrors?

What we've learned is that there are 3 pillars to fostering a existent modify in human rights and conflict resolution policy: field enquiry to learn what is really happening in the conflict zones and what needs to be done, high-level advancement to deliver the message to the people who decide policy, and domestic political pressure from a constituency that cares almost these issues and takes them up with their elected officials.

This concluding ane often goes missing. Sustained and robust campaigns by organized citizens are needed for maximum impact. Fostering these constituencies must exist our focus.

Will the Usa pb efforts to protect people when they are being systematically annihilated past predatory governments or militias? Will nosotros punish the perpetrators of crimes against humanity? Will we promote peace processes with high-level envoys and other back up? None of these options is beyond the realm of the possible; they are just matters of political will. If U.South. citizens and therefore the regime answer yep to these questions, millions of lives will be spared in the coming years.

The good news is that much of the suffering could come to an cease. It is inside our power. If the U.S. regime takes a lead role during each crisis marked by crimes against humanity, our chances to prevent or end these crimes increases dramatically. If the U.S. government had taken a leading function in three areas of policy — peacemaking, protection, and punishment — these crimes could have been prevented or stopped. If U.S. citizens and their authorities increase their activism and piece of work to build an international coalition to stop mass atrocities, major changes are possible.

Despite what you may run across on the evening news, there are encouraging signs of progress. Indeed, thin and desultory news coverage of Africa focusing solely on crises there has led to a "conflict fatigue" associated with the continent as a whole. Past ignoring the positive news, U.S. and European media risk fostering a dangerous tendency to dismiss the entire continent as hopeless. Then when wars erupt and their attendant human rights abuses emerge, the response — if there even is 1 — is often tentative and muted, and conflict-ridden countries hands descend into a complimentary-fall. We remember these conflicts are not just an affront to humanity; they are the greatest threat to overall progress throughout the African continent.

Yet despite the many obstacles, there is good news coming out of Africa every day. There has been a motion away from dictatorships toward commonwealth in many countries, and a commitment on the part of many African governments to fiscally responsible economical policies focused on alleviating poverty. Peace agreements have been forged in countries which only a few years before had been ripped apart by war and crimes against humanity. Witness the tragic tales of Liberia, Sierra Leone, Angola, Mozambique, southern Sudan, Rwanda, and Burundi, all of which had horrific ceremonious wars that came to an end, laying the groundwork for huge positive changes.

So that is the bespeak. If we can prevent and resolve these wars that pb to such devastation, one of the biggest reasons for Africa's misery and dependence will exist removed. By giving peace a risk, nosotros give millions and millions of Africans a run a risk.

Nosotros take identified the 3 Ps of ending genocide and other crimes confronting humanity: Protect the People, Punish the Perpetrators, and Promote the Peace. (We will describe these in detail in Chapter 9.) If the government of the globe'southward sole superpower, the United States, motivated by the will of its citizens, takes the lead globally in doing these three things, crimes against humanity can come to an terminate.

The decisions we demand to make to protect those who are suffering are clear, and the sooner we decide, the more lives volition be saved.

That is our choice.

Overcoming Obstacles to Action

So if it is equally easy equally that, why don't nosotros practice it? Mostly it is what we telephone call the Four Horsemen Enabling the Apocalypse: apathy, indifference, ignorance, and policy inertia. The U.S. authorities simply doesn't want to wade besides deeply into the troubled waters of places like northern Republic of uganda and Congo. We did once, in Somalia, and the resulting tragedy of Blackness Hawk Down — when eighteen American servicemen were killed in the streets of Mogadishu — made everyone nervous about recommitting any effort to African war zones nosotros don't fully understand.

As nosotros all know by now, during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, American citizens — to the extent that they even heard about what was happening — largely averted their eyes, and as a consequence the U.S. government did nothing. Like averting occurred during the 1975–1979 genocide in Kingdom of cambodia, from 1992 to 1995 in Bosnia, and even during the Holocaust. As our friend Samantha Ability documented in her book on genocide, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, this is the usual response to horrific crimes against humanity — disbelief in the totality of the horror and a 18-carat hope that the trouble will become away.

Somalia's Black Hawk Downwardly actually provides the wrong lesson. Instead of running away from these crisis zones, nosotros could protect many lives, and practise so much expert, if nosotros gave a little more than of our time, energy, and resource, in ways that sympathise the local context. In most cases, we don't take to transport 30,000 U.S. Marines every time there is a problem, though working with other countries to apply military force is sometimes necessary. Diplomatic leadership in support of the Three Ps (Protection, Punishment, Peacemaking) is what it takes to make a substantial departure.

Across indifference and the ghosts of Somalia, responding to Darfur has an additional obstruction. Sudanese government officials, who were close to Osama bin Laden when he lived in that country from 1991 until 1996, are now cooperating with American counterterrorism authorities. The regime in Khartoum rightly ended that if they provided nuggets of information about al-Qaeda suspects and detainees to the Americans, the value of this information would outweigh outrage over their state-supported genocide. In other words, when U.S. counterterrorism objectives meet up with anti-genocide objectives, Sudanese officials had a hunch that counterterrorism would win every time. These officials have been right in their calculations so far. As of this writing, well-nigh the end of 2006, the U.s. had washed little to seriously face up the Sudanese government over its policies.

In order to win the peace in Sudan, we must first win an ideological boxing at home. Nosotros must prove that combating crimes against humanity is as of import as combating terrorism. Often, as in the case of Sudan, the pursuit of both objectives doesn't have to be mutually exclusive. History has demonstrated that Sudanese authorities officials alter their behavior when they face genuine international diplomatic and economic pressure. If we worked to build strong international consensus for targeted punishments of these officials to meet both counterterrorism and man rights objectives, they would comply.

The policy boxing lines are clear. On the one paw are the forces of the status quo: officials from the U.s., other governments, and the UN who are inclined to look the other way when the alarm bell sounds and simply send food and medicine to the victims. They believe that the American public and other citizens around the world do not care enough to create a political cost for their inaction. These officials are allowed to remain bystanders because of complicit citizens who know about what is happening but exercise not speak out, giving the officials an excuse to do cipher.

On the other hand are a growing group of Americans, a canaille band of denizen activists all over the U.s.a. who want the phrase "Never Again" to mean something. They desire the beginning genocide of the xx-get-go century, Darfur, to exist the terminal. Led principally by Jewish, Christian, African-American, and educatee groups, they have slowly begun to organize. Nevertheless far more needs to be done to overcome the institutional inertia in U.S. policy circles. These groups are joined past an fifty-fifty smaller but determined core of citizen activists in other countries who are trying to build a global civil gild alliance to face crimes against humanity.

Who wins this battle volition determine the fate of millions of people in Darfur and other killing fields.

That is our mission.

A Citizens' Motion to Confront Mass Atrocity Crimes

Our friend Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times has written near a "citizens' regular army fighting to save" millions of lives in Darfur. Later describing some of the boggling efforts of ordinary citizens around the country, including fund-raising by immature American kids, Nick wrote, "I don't know whether to be sad or inspired that we tin plow for moral guidance to 12-year-olds."

Well, we are inspired.

Samantha Power has written about the "bystanders" who practice zip when genocide occurs and the "upstanders" who human action or speak out in an endeavour to finish the atrocities from continuing. Her book highlights the "upstanders" and "bystanders" of the last century. We all take the capacity to be "upstanders." The more than of us there are, the better the chances that these kinds of crimes volition not be allowed to occur in the twenty-first century.

It is up to us.

For us, Don first got interested in these problems through the motion-picture show he made, and so through connecting up with John, who had gone through his own process of growing awareness and discovering a whole universe of Americans who are getting involved and trying to brand a difference. We desire to show that information technology is possible to care enough to change things. We want to remove all excuses and impediments to private activity, because such actions — collectively — do brand a deviation.

Throughout American history, social movements take helped shape our regime'southward policy on a variety of issues. Often in the outset, their appearance was not widely recognized as much of a movement. We believe we are witnessing the nascence of a small but meaning grassroots movement to confront genocide and — we hope, over time — all crimes against humanity wherever they occur. A campaign like ENOUGH is but one manifestation of that endeavour, and we describe many others later in the volume.

Student groups are forming on hundreds of college campuses (and hundreds more high schools) specifically to heighten awareness and undertake activities in response to the genocide. Synagogues and churches are property forums and starting letter-writing campaigns all over the state. National organizations — some faith-based, some African-American, some man rights-related — are running campaigns in every city. Celebrities are getting involved, taking trips and speaking out against the genocide. Afterward all of the hollow pledges of "Never Over again" dutifully made by politicians and pundits, networks of concerned Americans are taking matters into their own hands and enervating policy makers practise more to end the crunch in Sudan.

One of the best things about this growing move is that it is nonpartisan. And then much of the venom that marks Washington these days — the red state/blue state divide — has been set aside. We always hear how politics makes strange bedfellows. How strange it must have been for some of the conservative evangelical members of Congress to observe themselves agreeing with some of the most liberal members the Congress has always seen!

How the world responds to genocide and other mass barbarism crimes represents one of the greatest moral tests of our lifetime. In the face of genocide halfway around the world, can American citizens — acting individually and in groups — peradventure aid in stopping these atrocities?

Admittedly!

Nosotros go on to be convinced that the growing chorus of outrage, from Florida to California, can stop war crimes and reduce the cries of agony in places such equally Darfur. The U.South. government tin accept a leading part in stopping atrocities, in most cases without putting U.S. forces on the ground in big numbers. However, the only ways by which U.Southward. policy tin change, and thus the only way mass barbarism crimes tin can finish, is if U.S. citizens raise their voices loud enough to get the attention of the White House and forcefulness our authorities to change its policy.

To encourage and embolden you, our readers, to join in this move to bring an cease to genocide effectually the world, nosotros offer Six Strategies for Effective Change that you equally an private can apply to influence public policy and aid save hundreds of thousands of lives:

-Raise awareness

-Raise funds

-Write messages

-Call for divestment

-Join an organization

-Lobby the government

Ultimately, this volume is most giving meaning to Never once more. In brusque, this is a handbook for everyone who thinks that one person cannot make a difference, for those who feel that what happens half a world abroad is not their responsibility, and for everyone who cares simply doesn't know where to start making a positive difference.

We want to tell that story.

Beginning, though, in the interest of full disclosure and since it is, subsequently all, our book, we volition tell you our stories....

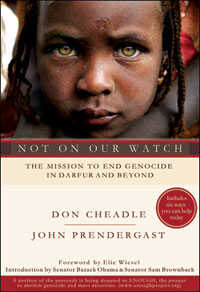

Excerpted from Non On Our Watch by Don Cheadle and John Prendergast. Copyright 2007 Don Cheadle and John Prendergast. All rights reserved. Published by Hyperion. Available wherever books are sold.

Source: https://www.npr.org/2007/05/01/9928999/not-on-our-watch-a-mission-to-end-genocide

0 Response to "Confronting Genocide Never Again Darfur Violence and the Media"

Post a Comment